Abraham and Augusto clamber their way down the brushy slot canyon over boulders and between thorny branches. Baja summer sun and the rigor of their toil soak their long-sleeved shirts with sweat, but they are elated. They have bagged the prize of the hunt: a documented observation of the elusive Galium carterae.

They saw it first from the top of the slot. An unassuming, scruffy patch of dark green caught Augusto’s attention as we passed a 5-meter side gash in the ground whose floor I couldn’t make out in the shade and shrubbery, but peering over the edge gave me the willies.

Sprigs of tiny pointy white leaves stood out like flowers from a distance against the Galium’s greenery and stole the show from even smaller pale-yellow flowers. The botanists studied it through cameras, binoculars, and cameras aimed through binoculars. Abraham read and reread a scientific description of the subshrub through his round-framed glasses and Augusto scribbled studiously in a small notebook.

So exciting was their find that they decided to launch a ground-level assault, involving negotiating our way down the mountainside to the outlet of the slot and bushwhacking in.

So exciting was their find that they decided to launch a ground-level assault, involving negotiating our way down the mountainside to the outlet of the slot and bushwhacking in.

I stand with Alfonso, a ranchero in a black cowboy hat and a grey moustache, near the outlet of the slot, awaiting the botanists and overlooking crumpled origami mountains. His kind eyes know well the land he surveys below us.

The eastern face of the range is steep and textured, a reddish shade of brown. A wide landscape of pale latte-colored plateaus gracefully slopes to the west, punctuated by grey rockslides. Mountains tinge with blue in the distance, fading into a horizon of marine fog. A creamy ribbon wanders through occasional patches of shy green along the bottom of an arroyo that bends its way toward the Pacific.

“Nobody lives in any of the ranches there any more,” he says.

For over 40 years, more years than the botany boys have been alive, Alfonso has chased “la bestia” burros, mules, cows, goats and horses, through prickly thickets and across loose rocky mountainsides. He is a ranchero, vaquero, cowboy. He knows exactly where in the hidden folds of mountain are the 3 puddles of water that support days and nights afield. He recognizes the desiccated vine of a kind of wild sweet potato that can be dug up with a conveniently shaped rock, dusted off, peeled with the ever-handy blade, and eaten raw, or cooked in a variety of ways if one has the utensils and inclination. He’s applied lomboy and sliced cactus to injuries incurred along the way. He knows the locations of at least 5 abandoned ranches in these drainages.

We chat as we wait for the boys to arrive with their cameras and notebooks, their day packs and their grins, bearing evidence of success on this exploratory botany expedition organized by Sula Vanderplank of Conserva Loreto and funded by Baja Rare, a program of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

Alfonso turns to me and asks about this expedition in general, “Why do they do this?”

It’s an honest question.

Though he’s puzzled, Alfonso has a lot invested in the effort.

Not only does he know the area and provide the animals that carry us to our basecamp where he stashed our food and camping gear the day before we started, but he rebuilt the trail up the steep face of the Giganta and made getting here even possible. Storms obliterated the trail more than a decade earlier and nobody had passed this way since.

Rebuilding it took a year of moving boulders by hand, backfilling deep holes by shovel and chopping back vengeful desert plants. On our ride up he points out a boulder that crushed his finger during his efforts, an injury that left him with permanent nerve damage.

Despite his labors, it’s still not an easy trail. We’re instructed to hold the mane of our horse or mule and lean forward as they lunge up steep hillsides. We balance breathlessly as our mounts position themselves to jump down precipices or skid on pebbles over the slickrock. We’re invited to walk the switchbacks where the animals awkwardly pivot themselves on the turns above dizzying drops. This is not an outing for the faint-hearted.

Our expedition started up the Primer Agua 4-wheel drive road on Wednesday May 15, 2024. My 56th birthday. At the ranch Alfonso shares with his wife Paula, we shift into muledrive. We’re joined for safety and assistance on the ride up by Luis, a handsome young vaquero on a super-charged blood bay horse with bulging neck muscles, wild eyes, and hooves that never stop moving. Luis, they say, can ride anything. His spurs jingle the soundtrack of our day.

My mount is Principe, named for a Mexican cookie. His coat of chestnut brown is flecked throughout with white hairs. From a distance he appears almost pink. He stands statue without being tied as we secure my day pack behind the saddle and I mount up, with my flappy, awkward, oversized chaps.

My mount is Principe, named for a Mexican cookie. His coat of chestnut brown is flecked throughout with white hairs. From a distance he appears almost pink. He stands statue without being tied as we secure my day pack behind the saddle and I mount up, with my flappy, awkward, oversized chaps.

A horse’s ears are its radar, swiveling this way and that. Like most animals, the horse’s survival depends on its alertness to its surroundings. Horses hear in ranges both higher and lower than humans, and more sensitively. Their ears pivot 180 degrees and can tilt, prick, droop and flatten, also expressing mood and concentration. Aimed forward, they can indicate interest in what’s ahead.

Principe’s ears swivel independently as he concentrates both ahead on the trail and back on my cues like leg squeeze to move, pressure on reins to turn. His ears tell me he’s relaxed, agreeable, and willing to work in partnership with me.

There are parallels between riding a horse and being a human in the environment. Through I grew up riding horses, it’s still amazing to me that such a large and powerful animal does our bidding. How much of the cooperation is born of trust and collaboration, and how much of dominance?

When we change the landscape around us, the collaboration or dominance question also applies. Are we working within natural principles or putting a house or a road where Nature needs the flexibility to move, like a waterway or a coastline? Are we growing food with sustainable practices, or fundamentally changing the relationships of the land through monocrops, pesticides and irrigation?

Horse and environment are bigger than we are and have the capacity to do something unexpected. It is wise to stay alert for rebellion, or a return to a longer-term equilibrium than we planned for. Like the ears of the horse, we keep swiveling, keep listening.

This botany expedition is one swivel of our horse ears. Up the mountains this week we seek plants last documented decades ago and other rare or strange life we may stumble across on the way. What are the plants telling us about this place? About land, weather, climate? About change? About our tenancy here?

Alfonso and Augusto ride side by side chatting, ranchero and botanist. The round white rump of Alfonso’s mule Bonbon and the narrow bay rump of Chuckwaka bob and sway under the men who periodically burst out with the impassioned cries of classical Ranchero songs.

Alfonso and Augusto ride side by side chatting, ranchero and botanist. The round white rump of Alfonso’s mule Bonbon and the narrow bay rump of Chuckwaka bob and sway under the men who periodically burst out with the impassioned cries of classical Ranchero songs.

As we ride, botanist Augusto correlates his vocabulary with that of Alfonso. “No, that’s not palo verde.” Alfonso surprises all of us about the tree with the green trunk which the rest of us lowlanders call palo verde. “Palo verde is the one with the TRULY green trunk up there.” Alfonso motions toward the mesa where we’re headed.

Language is a tool through which we see the world. When we hold the lens of scientific names, we think in categories. The relationships are those of family and process. Who is your relative? How long back did you split from that group?

“Palo verde de verdad” Alfonso’s REAL palo verde, on the mesa is Parkinsonia praecox, an early-flowering species of palo verde. Palo verde is a commonly accepted general name for green-trunked trees in the genus Parkinsonia, named in honor of English botanist John Parkinson (1567-1650).

iNaturalist.org is a free global database of species to which we’ll upload our observations from this expedition. Our photos will be scrutinized and identified and will be available for the scientific community. The unfiltered, worldwide version (iNat) is rendered in English. Naturalista.mx is the same database filtered for Mexico and presented in Spanish. The scientific names are the same. Some plants have common names in Spanish is so well known that the Spanish is used on the global site as well. iNat gives its common name of Alfonso’s “palo verde de verdad” as Palo Brea.

Palo in Spanish means branch, wood, or stick. Brea means pitch or tar. Wax from pustules on the bark of palo brea has been heated and used as ranch glue. Interestingly, brea in old English was used as a title for noble families living on a hill and came to simply mean hill, appropriate to this tree that typically grows at elevation in Baja.

“What do you call this one?” asks Augusto of the palo-not-verde we’re passing.

“Mesquite.”

Later Augusto inquires, “How many species of mesquite do you know?”

The question baffles Alfonso. All thorny, tree-like beings were mesquite. Their differences didn’t matter so much as you could cut branches from any and feed them to your hungry mule. That was a plant relationship in the cowboy’s world.

We pass a colony of pale cacti with a grey stubble of spines at the tips of some branches. I learned it as Old Man’s Beard. iNat calls it senita, but it’s commonly called garambullo around here. Lophocereus schottii probably rolls nicely off the tongue of come bespeckled botanist but sounds to me like a lazy star. Lopho: lazy. Sirius: the brightest star in our northern sky. Shotty-Ay: maybe it was a shooting star? This is what you get when you invite an English major / kayak guide on a botany trip. I am a late invitee/volunteer, replacing a key member who couldn’t make it. Obviously not for my botany prowess, but I have outdoor experience and a penchant for nature-nerding and posting observations on iNat.

The trail narrows from a vehicle track to single file through the arroyo and along it’s brushy sides when the arroyo is too bouldery for our four-footeds to negotiate. The essential nature of the leather chaps I’m wearing over my legs becomes evident as we push through all sorts of bush. I wish I had chaps for my head as my elegantly tall Principe delights in passing just below thorny mesquite branches.

The trail narrows from a vehicle track to single file through the arroyo and along it’s brushy sides when the arroyo is too bouldery for our four-footeds to negotiate. The essential nature of the leather chaps I’m wearing over my legs becomes evident as we push through all sorts of bush. I wish I had chaps for my head as my elegantly tall Principe delights in passing just below thorny mesquite branches.

We reach a mesa, rest the sweaty bestia, and consider investigating plants along the eastern cliff-edge of the mesa. Below his dark grey floppy brimmed outdoor hat, Abraham slides his red buff off his face for a drink of water. His peaceful, bookish features behind round glasses are clouded with worry about being out in the sun at 1pm, the heat of the day. I point out the clouds and the refreshing breeze and calculate from Alfonso’s “half an hour to camp” estimation that we’ll be in the shade by 1 if we explore the cliff for an hour. He agrees and off we wander with our cameras and notebooks while cowboys Alfonso and Luis have a smoke.

Crossing the mesa we encounter Alfonso’s palo verde de verdad and take photos of it while Alfonso and Luis adjust the saddles further back and tighten the girths on our mounts for the decent into a drainage that leads to the Pacific. We’ve crossed the Giganta divide.

Horses may be generally faster, but mules are more sure-footed in rough terrain, especially downhill. Principe lowers his head to inspect the pebbles over the slickrock in a few touchy places and pauses to arrange the placement of his hooves for the tricky drops. On a steep, loose section, my mount does something between walking and skiing. For a moment I am horse-surfing down the mountain.

We come to a wide shady mesquite tree tied to a strawberry blonde mule. A white plasti-burlap costal of food hangs from a stout branch. A pile of our camping gear sits nearby. A few steps beyond the tree and its companions is a puddle of clear water in grey rock, about the size of a long-bed pick-up truck but only half a tire deep. It feeds some mini-cascades waving with furry green algae. A lower green pool fades into the gravel. Insects, lizards, birds, amphibians, and wiggly aquatic things flit and slither about.

Alfonso points out good camping downstream of the water and we decide it’ll make a fine home for our two nights on expedition. We carry all but the mule and the tree to the indicated shady patch of gravel, then settle in and pass around the bottle of Huichol hot sauce to season and moisten burritos of machaca (dried, pounded beef) on homemade tortillas. Our mounts lower their heads for long drinks from the green pool.

Luis says adios and turns his dancing horse and singing spurs back down to the ranch.

We turn our curiosity down the arroyo. There’s a polyglot of languages in our party. We converse in Spanish. Abraham and Augusto scamper on in the Latin of scientific names, which runs right by Alfonso. I catch some, but struggle to understand our different pronunciations. I verbalize in a stiff, book-learned, English-influenced Latin while they riff along with Spanish influence, formal education, and perhaps having actually heard someone say the scientific name before.

I feel the rush of recognizing a plant and turn to call it by name to share the experience. But here, my English names for plants are useless and confer no connection but my own memory.

The boys get excited about a chubby pale green rosette growing on the cliff-face. A Dudleya desconocida. Unrecognized succulent. Alfonso sits on a rock shelf nearby and watches us reach, climb, photograph, and chatter enthusiastically. Who should we name it after? Exhausting both my usefulness in pursuit of the Dudleya and my curiosity about nearby plants, I join the ranchero.

The boys get excited about a chubby pale green rosette growing on the cliff-face. A Dudleya desconocida. Unrecognized succulent. Alfonso sits on a rock shelf nearby and watches us reach, climb, photograph, and chatter enthusiastically. Who should we name it after? Exhausting both my usefulness in pursuit of the Dudleya and my curiosity about nearby plants, I join the ranchero.

Conversing about the Dudleya, I mention the Spanish name siempreviva. However, to Alfonso, siempreviva is a different plant altogether. He shows it to us the next day high on the mountainside: a dried-up brown fern which he said simply turns green and uncurls its tiny fronds after it rains. None of the rest of us have ever seen it before.

For Alfonso these plants we’re fawning over are old friends or at least casual acquaintances oft passed and occasionally greeted.

On our way back up the arroyo to camp, he detours up a tributary and leads us without fanfare to a healthy congregation of the little Dudleya. “Unrecognized” is a relative thing.

His connection with the plant life here is contextual and experiential, a different kind of intimacy than scientific study with the life that is the plant.

Our detour takes us through the site of a former ranch, now just memories, a cow skull wedged in a thorny bush and a few broken bits of glass. We can see a mountain ridge from here and discuss tomorrow’s objectives. Rare plants would most likely be found near water and on steep, high, north-facing cliffs, we speculate. To the mountain we would go, and on the way back, seek moisture or shady crevices.

Back at camp, Alfonso butts two rectangular rocks against the cliff wall to make a fireplace, and within minutes has some dry branches burning to heat water for coffee. Augusto heads out to place a game cam on a trail he saw earlier. Abraham and I sort through the food to see what we have. Once there are coals, we heat cans of imported beef stew, joking how the can and its contents resemble dog food. Good ranchero that he is, Alfonso will have none of it but chews on his machaca burritos from home.

A breeze keeps the night cool and brings the hoots of a great horned owl.

I scramble eggs for breakfast in the soot-blackened frypan over the morning fire. Hot coffee melts and reshapes the boys’ makeshift mugs of square electrolyte bottles with the tops cut off.

Alfonso has taken the two horses up to better forage for the day and returned before we’re ready to march. And march we do. We have miles to cover to reach that high ridge, and he has seen how slowly we can cover ground looking at plants.

After about 15 minutes, we pass the 2 horses. Occasionally we pause to survey the landscape ahead and agree on route, but mostly we tromp on as fast as we can. A passionflower appears to be a different species of Passiflora than the ones we’d seen at lower elevations. Photos must be taken. We joke about finding important plants so we can catch our breath. Alfonso suffers us with patience.

At 65 years old, Alfonso out-hikes all of us in his black leather boots, uphill, downhill, chopping trail, or leading 2 horses through the brush on nothing but a cup of coffee in the morning and occasional sips of water from the plastic gallon he filled from the cleanest part of the puddle before we set out. He carries it on a loop of well-worn webbing over the shoulder of his faded and worn blue button-down shirt. He carries nothing else, though a folding blade and a small machete appear in his hands when he wills them into being at a time of need.

We traverse a sloping hillside, cross a small arroyo with a scenic stand of palo blanco, tromp up a rise, and zigzag between bushes across an almost flat stretch.

We all wear jeans, long sleeves, and boots even in the heat, and are grateful for the protection of the thick materials as the thorns are hungry. When pressing our way between bushes, for a while we could choose the non-thorny flexible branches of lomboy or matacora and lean into them, avoiding whatever thorny shrub was on the other side. Increasingly the choices are between thorns and spines, thorns and more thorns, or thorns and vicious rabid thorns. Palo Adán Fouquiera diguetii, Dog Poop Bush Ebenopsis confinis and a thorny devil that shows no respect and knows no boundaries, Mimosa distachya. Intimate with plants alright, this expedition.

During our periodic short breaks, Alfonso hunkers below the branches of shrubs in the shade. When I use the moment to wander over to a cluster of rocks and start observing the hunting spiders, Alfonso takes it as time to move on. During one break, I notice elongated spiral snail shells, sun-bleached to white. I later learn from an iNat mollusk specialist that this is the first observation of this species on the iNat database. Berendtia taylori, a land snail described in 1861 was originally mis-classified the same way I mis-classified it when I posted it.

That’s the beauty of working in community where curiosity is rewarded. Ignorance is not a barrier to participation. Being wrong is just a doorway to learning.

Plants without English common names on iNat have helped me learn Latin names. What I know from the Baja California Plant Field Guide as rama parda, the smelly purple trumpet that almost always blooms, is Ruellia californica. But if I start to identify it online as “Rama” the database offers me earthworms and little fishes.

Plants without English common names on iNat have helped me learn Latin names. What I know from the Baja California Plant Field Guide as rama parda, the smelly purple trumpet that almost always blooms, is Ruellia californica. But if I start to identify it online as “Rama” the database offers me earthworms and little fishes.

At the higher elevations we’re surprised to notice Ruellia californica’s slightly fuzzy, odiferous leaves are instead shiny and fit for polite company, being the subspecies Ruellia californica peninsularis. Learned: the Ruellia californica I know from the islands and little elevations is actually the redundantly named subspecies Ruellia californica californica.

Eventually we make it to a cliff face, along which we follow Alfonso to a place we can scramble up, and it opens a new level. A plateau leads to a ridge that swoops up a steep hillside to the big north face. It’s evident immediately that there are different plants up here.

Several tall Elephant Trees Pachycormus discolor raise branches high with creamy foliage or tiny blossoms, it’s hard to tell from the ground. A ragweed holds 6” long leaves aloft like jagged flags. We claw and scramble to a little perch on the very northeastern tip of the steep scarp. Abraham recognizes a rare Buddleja corrugata gentryi he’s not expecting to see here. It has light green fuzzy leaves and stems and a tower of over 30 compact orange blossoms crammed together at the tip. Augusto takes careful notes. Coordinates. Altitude: 1,000 meters. Habitat: cliff face. Neighboring plants, like the Agave sobria it embraces.

Alfonso hunkers nearby in the shade of a cliff and a colubrina shrub. I scramble just a little further upward to investigate a pocket of flora and am rewarded with the Dudleya species as well as a delicate white blossomed Drymaria I recognize from an encounter on Isla del Carmen after a rain and from a shady crevice up in a canyon near Tabor.

From here we can see a fog bank on the Pacific. Some of these plants suggest the fog visits here on occasion, most notably a stringy lichen that reminds me of ones I’ve seen in the Pacific Northwest of the US and on the northern Baja Pacific coast. It’s in the family Ramalinaceae, appropriately known as “sea fog lichen”.

Up here on the on the spine of the Sierra la Giganta overlooking the Gulf and the Pacific, we are on a tectonic ride to the northwest, but so slowly we won’t notice it in our lifetimes. A collision of tectonic plates formed these mountains and their neighbors, and a spreading rift opened the gulf that made them a peninsula.

Knowing this leads to a question of scale. The plant species we are studying are snapshots in a process of adaptation and extinction. Change is constant, and it is linear or cyclical depending on the scale at which you consider it.

Knowing this leads to a question of scale. The plant species we are studying are snapshots in a process of adaptation and extinction. Change is constant, and it is linear or cyclical depending on the scale at which you consider it.

A plant sprouts, grows, reproduces and dies. Linear. From its seeds sprout the next generation. Cyclical. Mountains change so slowly we view them as static, but just ask Alfonso who spent a year rebuilding the trail if rocks don’t flow downhill. Erosion flattens mountains. Linear. Tectonic forces shape new ones. Cyclical, though geology is complex because its minerals mix and react with molecules from plants, air, sea, animals, and other life and its products. It’s a whole planet recycling system.

Everything is connected, including in ways we still don’t completely grasp. As humans, our great gift of understanding lets us recognize this. It also lets us see the worldwide epidemic of species extinctions and the deterioration of natural systems.

Linear is the path to extinction. There have been five major extinctions before this, and each one opened new opportunity for different kinds of life. Cyclical. If mountains recycle and species have a shelf life, why does a little Dudleya stuck high on a cliff matter?

Of course, for those going extinct it kind of sucks. Those adaptable enough to live through upheaval embrace change to succeed. Where are we in this picture?

Can we slow the change? Hold onto a quality of life so we and those we love live in comfort a little longer? Feel like we weren’t the oafs who destroyed the beauty and functional systems we inherited?

Aligning our use of natural resources and ways of being in the world with the longevity of biological communities, genetic diversity, and ultimately the environment we live in is the work of conservation.

Conservation is for us.

Conserva Loreto, which put together this expedition, is “a program committed to the protection and strengthening of Loreto’s conservation areas, for the benefit of people and biodiversity. Our mission is to conserve natural resources for future generations through Research, Education and Social Justice. We support an environment in which local communities not only survive, but thrive, with access to rich and diversified biological resources.”

Conserva Loreto, which put together this expedition, is “a program committed to the protection and strengthening of Loreto’s conservation areas, for the benefit of people and biodiversity. Our mission is to conserve natural resources for future generations through Research, Education and Social Justice. We support an environment in which local communities not only survive, but thrive, with access to rich and diversified biological resources.”

Here we can easily wander off this prickly dry hillside into Philosophy, Religion, Psychology, Ethics. Where concepts of soul and purpose weave into the fibers, where fear and scarcity lurk, where fairness is weighed. Where we try to make sense of our experience of the world in a larger way.

Instead, we make our way down the mountainside. We pass a crevice in the earth where Augusto exclaims at a plant he sees growing on the cliff wall. Could this be the Galium carterae on our Most Wanted rare plant list? Left hand scribbling earnestly, he makes his notes while Abraham dictates.

I find myself standing with the vaquero as we wait for the boys to emerge from the canyon victorious with their observation. And Alfonso asks that question of all questions. Why?

Why do we scour mountainsides for shy plants? Why do we go to great efforts to describe and document plants? I look out over the folded land and breathe for a moment, considering.

“To understand the world,” I finally say. “This is one way: describe the plant, capture its image, note its habitat, parse its genetics.” I turn to look at him. “Living with it as you do is another way.”

Back in camp Augusto checks his game cameras and Abraham and I mix canned tuna with canned veggies to make a quick and easy no-cook dinner.

After we eat, Alfonso offers us some of his understanding of the world. A summary of 40 years of observing includes a lament on climate. “The gentle winter rains don’t fall anymore,” he says. “The plants start to grow after a little sprinkle, but seeds aren’t developing fully enough to germinate the next generation. The rain that falls in winter, if it falls at all, may only dampen one place or another, but it doesn’t fall everywhere or as often as it once did. There isn’t pasture for the animals. The bushes, garabatillo, are all dry with no leaves and a lot fewer plants than there used to be.”

We all bear scars of battle from that cursed bush today.

“Imagínate!” exclaims Augusto with a grin. “There used to be more of them!”

Alfonso and Paula don’t have anyone succeeding them on the ranch. They are one major injury or the death of a partner away from shutting down their ranch, too. Then there will be no more active ranches in this watershed either, like on the Pacific side. He does not talk nostalgically about it, just states it, but it’s part of an epidemic of extinction of ranches and people living intimately with this land.

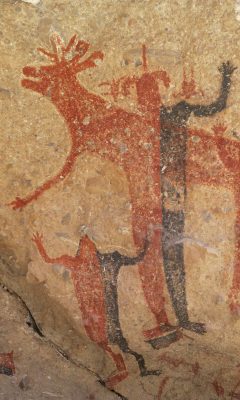

I visited the Sierra San Francisco cave paintings in the central Baja peninsula on a mule trip a few years back. A friend pointed out similarities of lifestyle between the artists of the paintings and the vaqueros who led us to see them. Depicted on the rock were deer, rabbits, people, birds. Arrows. It was a culture whose resources came from plants, animals, rock.

Indigenous people lived a life of deep knowledge of the plants and animals. They survived in an area immensely challenging to do so. Though no indigenous cultures remain in southern Baja California, some of their knowledge lives on in the culture that now inhabits the more inaccessible parts of their homeland, protected from rapid change by the landscape itself.

The equipment we used and some of the food we ate were direct products of local animals or local plant technology. Leather saddles and saddlebags, rigid rawhide containers, crates of cactus ribs. Machaca. The animals supporting the ancient culture and the animals of current cultures differed, but both cultures sustained themselves in relationship with the land, animals and plants.

Cultures and people who are intimate with a place hold information. Not just information like a dry seed in the hand, but experience alive in relationship, alive with the exchange of nutrients and energy. Alive with the perspective of time.

If we are here to understand, what have we come to understand? We are here in the name of science, which holds information in books and databases and drawers of dried plants. These are valuable for bringing life into the halls of study, and study is essential for improving how we live in the world, but study needs to remember that the thing brought inside for analysis and the images stored in electronic tables are missing something.

The spark of sun, droplets of fog from a distant sea, the shade of a neighboring plant, the hidden way their roots intertwine and break rock and hold hillside. The home provided to the beetle. The pollen to the insect. The lunch for the spider who awaits the pollenating insect. Dried leaves for the millipede. Recognition in the eye of the passing vaquero.

Our short time in these mountains has brought home that relationships matter. Relationships of climate and plants, of plants with each other, of plants with animals, of us with resources, and beyond that.

Our short time in these mountains has brought home that relationships matter. Relationships of climate and plants, of plants with each other, of plants with animals, of us with resources, and beyond that.

A common purpose brings us together. Our differences enrich us. The botanists asked questions of the plants the rancher had never thought to ask. The rancher held knowledge through a lifetime of noticing, and perspectives the botanists hadn’t yet pondered.

Relationships are built of shared experiences. In the process of gaining understanding, of seeking, we gained something more profound than information. We lived experiences together in this place of mountain desert.

Relationships are built over time, built of these experiences in a place. For conservation to succeed, the conversations about it need to include people whose relationships have been long and intimate with place, land, plants, animals, sea. Conservation is a social issue as well as an environmental and scientific one.

Conservation is an idea. Information is the seed. Relationships are the soaking rain that nourish its growth. Community can bring to life the seed of sustainability offered by conservation. Or stomp it into the dust, at its own eventual peril.

This means, dear Parque Nacional Bahia de Loreto (PNBL) and CONANP, please include community conversation in the development of new National Park plans. You will gain perspective on what issues are motivating people now. You will gain clarity on the non-governmental human resources available to mobilize to meet specific needs. Your community will gain an appreciation of the complexity of the voices and objectives around these spaces and their resources. Organizations and individuals will be energized to support something they have a voice in shaping, and could be enabled to contribute outreach, education, cleanup, research, monitoring, vigilance, etc.

You already know several issues of concern to your surrounding population of humans: access to wild spaces including beaches and sea and camping, fresh water supply, fair enforcement of existing rules, scientific support of harvest regulations and other management decisions.

There are people, groups, and organizations with a wealth of experience in the places you’re managing and planning to manage. In addition to the resources and goodwill you could gain, conversing with your community about objectives and how to meet them can help avoid ineffective strategies that cost time, money, and the loss of confidence of the community.

We ask because we care. Thank you.

And thank you for re-convening the Advisory Board for the existing Parque Nacional Bahia de Loreto.

We descend the steep east face of the Giganta on a Friday, pausing between switchbacks to observe another green and white Galium carterae subshrub and some other rare plants on the way.

We say our goodbyes to Alfonso and Paula at Rancho Saucito. Abraham catches a bus for La Paz and his studies at CIBNOR for a Masters in Botany. Augusto reconnects with the organizer of this expedition, Sula, and they begin to compile a scientific report from the trip.

I return to overseeing summer operations at Sea Kayak Baja Mexico, which include free-to-the-community paddlesports training and sponsored programs for schoolkids to connect with nature through paddling.

And we post our observations on iNat. Have a peek if you’d like. iNaturalist.org